Event Sourcing departs from traditional state-centric data management. Instead of treating the current state of entities as the primary source of truth, Event Sourcing recognizes that the sequence of changes—the events—contains richer, more complete information about what actually happened in your system.

Consider the difference between a bank account balance and a bank statement. Traditional CRUD systems store the equivalent of just the current balance:

- Account 12345 has $1,247.83.

Event Sourcing stores the complete statement:

- Account opened with $0

- Deposit of $2,000 on January 3rd

- Withdrawal of $500 on January 8th

- Interest payment of $12.50 on January 15th

The current balance becomes a derived calculation rather than stored state.

This mental model shift has profound implications. Events capture not just what the system looks like now, but the complete story of how it got there. This historical completeness opens up capabilities that are expensive or impossible to retrofit into state-based systems: comprehensive audit trails, time-travel queries, replay-based debugging, and the ability to ask unforeseen questions about your data.

Note that event sourcing doesn’t describe external APIs and systems.

Core Architectural Concepts

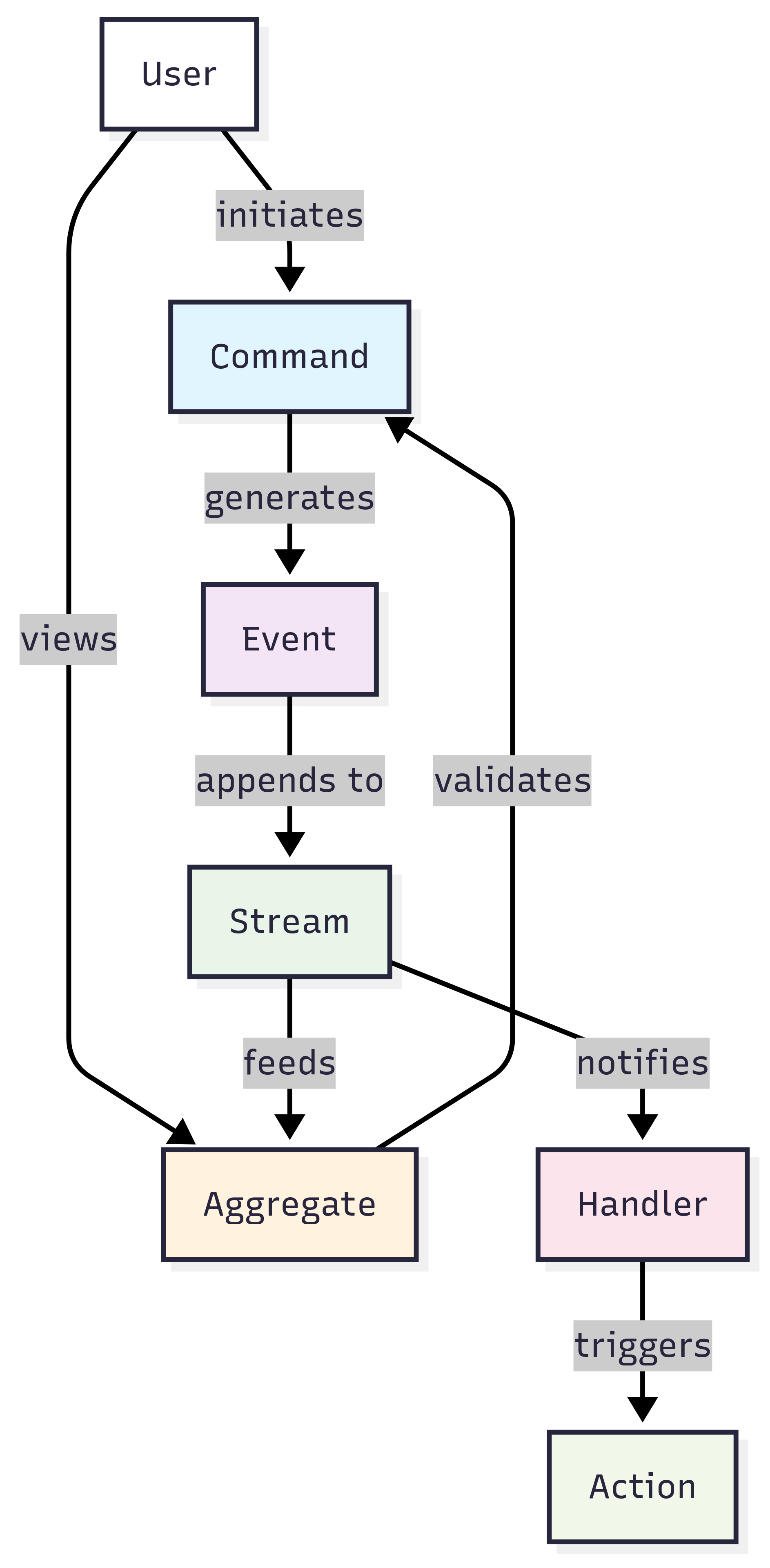

Event Sourcing frequently uses several interconnected concepts that form the foundation of event-driven architectures. These concepts are sometimes incorrectly used interchangeably, but they have distinct roles and responsibilities (so keep that in mind when reading other sources).

Events are immutable records of facts that occurred in the past. The key insight is that events represent something that has already happened, not something that might happen or should happen. CustomerRelocated is an event; RelocateCustomer is not. Events carry enough information to understand what changed, but they don’t prescribe how different parts of the system should react to that change. A well-designed event might include the customer ID, the old address, the new address, and a timestamp, but it wouldn’t include instructions about updating shipping preferences or recalculating tax rates.

Streams provide the organizational backbone for events. Each stream contains an ordered sequence of related events, typically centered around a particular entity or business process. Think of a stream as the complete history of a single customer, order, or project. The ordering within a stream is critical because it establishes the timeline of changes. Events in different streams can occur concurrently without ordering constraints, but events within a single stream have a definitive sequence that must be preserved. At scale, it’s common for streams to decompose to two technical things: a publish-subscribe channel for new events, and an append-only log for historical events query.

Commands represent the imperative requests that cause events to be written to streams. Commands express intent: ChangeCustomerAddress, ProcessPayment, or CancelOrder. Commands can be rejected if they violate business rules or if the system is in an inappropriate state. When a command succeeds, it typically results in one or more events being appended to the relevant stream. The separation between commands (requests for change) and events (records of completed change) provides clear boundaries for validation, authorization, and error handling. Commands are most open-ended, not constraining anything to happen within them: so commands that consult an external system or generate side effects are valid.

Aggregates serve as the computational layer that derives current state from event streams. An aggregate maintains the current state of an entity by processing all events in its associated stream. Importantly, aggregates are typically ephemeral—they can be reconstructed at any time by replaying their event stream from the beginning. Aggregates “remember” the last event they processed to enable incremental updates rather than full replays. For example, a ShoppingCart aggregate might maintain current items, quantities, and totals by processing ItemAdded, ItemRemoved, and QuantityChanged events. To keep regeneration idempotent, aggregate generation must avoid side effects like sending emails or updating external systems.

Event Handlers provide the reactive backbone of the system. These listeners monitor streams for new events and trigger appropriate responses. Unlike aggregates, which typically focus on a single stream, event handlers often coordinate across multiple streams or trigger side effects in external systems. An event handler might listen for OrderPlaced events to trigger inventory updates, send confirmation emails, or initiate shipping processes. From a technical perspective, it’s common to use event handlers to implement aggregates, but it isn’t necessary.

To illustrate these concepts working together, consider an e-commerce order processing system. When a customer modifies their cart, a ChangeItemQuantity command is issued. If the command passes validation (item exists, quantity is positive), it generates an ItemQuantityChanged event in the customer’s cart stream. The ShoppingCart aggregate processes this event to update its internal state. Meanwhile, event handlers listening to the cart stream might update recommendation engines, adjust inventory projections, or trigger abandon-cart campaigns if the cart becomes empty.

Benefits

Event Sourcing’s benefits become most apparent when dealing with complex business domains where understanding the evolution of state matters as much as the current state itself.

Auditability emerges naturally from the append-only nature of event streams. Every change to your system is captured with complete context: what changed, when it changed, and often why it changed. This creates audit trails that are difficult to tamper with or accidentally corrupt. For regulated industries, this capability often justifies Event Sourcing adoption by itself. The ability to build systems on append-only storage like WORM (Write Once, Read Many) drives also enables compliance with stringent data retention and audit requirements.

Consider a financial trading system where regulators require complete trade audit trails. Traditional systems might log state changes, but proving that logs haven’t been altered requires additional complexity. With Event Sourcing, the events themselves are the system of record, and their immutable, append-only nature provides inherent tamper resistance.

Scalable Reads are possible because aggregates can be computed independently and cached aggressively. Since events are immutable, you can safely replicate event streams across multiple read models without consistency concerns. Each aggregate or read model can be optimized for specific query patterns. A customer service application might maintain aggregates optimized for recent activity, while an analytics system maintains aggregates optimized for historical analysis.

This scalability shines in systems with diverse reading patterns. An e-commerce platform might need product views optimized for browsing (with search, filtering, recommendations), inventory views optimized for warehouse operations (with location, availability, reorder points), and analytics views optimized for business intelligence (with aggregated sales, trends, forecasting). Traditional systems often struggle to optimize for such diverse access patterns without expensive denormalization or complex indexing strategies.

Time Travel Capabilities allow you to reconstruct system state at any point in history. This isn’t just about viewing old data—it’s about running the same business logic against historical states to answer questions like “How many customers were eligible for our premium tier as of last quarter?” or “What would our current inventory look like if we had implemented the new pricing algorithm six months ago?”

This capability is invaluable for business analysis, debugging, and compliance. When a customer disputes a charge, you can replay their exact session to understand what they experienced. When a bug corrupts data, you can identify the problematic events and replay the system from a point before the corruption occurred.

Bug Fixing and Data Recovery become more tractable because the complete history of changes is preserved. When traditional systems encounter data corruption, recovery often involves restoring from backups and losing recent changes. With Event Sourcing, you can identify the specific events that caused the corruption, correct them, and replay the system forward. This surgical approach to data correction minimizes data loss and system downtime.

Challenges and Design Considerations

While Event Sourcing offers compelling benefits, it introduces significant complexity that must be carefully managed.

Write Scaling remains a fundamental challenge. Event Sourcing doesn’t magically solve write bottlenecks—it shifts them. While you can scale reads by replicating event streams to multiple aggregates, writes still need to be serialized within each stream to maintain event ordering. For systems with high write volume concentrated on a small number of entities, this can create bottlenecks.

Addressing write scaling typically requires thoughtful command partitioning strategies. Instead of having a single “UserAccount” stream, you might partition into “UserProfile,” “UserPreferences,” and “UserBilling” streams. This reduces contention but requires careful consideration of transactional boundaries and consistency requirements.

Architectural Complexity is perhaps the most significant barrier to Event Sourcing adoption. Traditional three-tier architectures with databases, application servers, and user interfaces are well-understood and supported by mature tooling ecosystems. Event Sourcing typically requires bespoke architectures complex enough to need custom tooling.

Standard databases and libraries are optimized for mutating shared state, not for append-only event streams and derived aggregates. Adding an index to improve query performance in a traditional system is straightforward; developing new read models in an event-sourced system requires more substantial engineering effort. The impedance mismatch extends to programming language ecosystems, where frameworks and libraries often couple domain logic with persistence concerns. Event Sourcing demands that these be distinct types with clear separation.

Event Design presents subtle but critical challenges that have long-term implications for system evolution. The granularity question—should you store fine-grained delta events or coarser-grained snapshots—affects both performance and flexibility. Fine-grained events like ProductTitleChanged and ProductPriceChanged provide maximum flexibility for future querying but can result in lengthy event streams and more code for event handlers and constructing aggregates. Coarser-grained events like “ProductUpdated” are more compact but may not capture the semantic meaning of specific changes.

Most successful implementations adopt a hybrid approach, using fine-grained events for business-critical changes that need detailed tracking and coarser-grained events for less critical updates. Commands can generate multiple events, allowing you to capture both the detailed deltas and higher-level business meaning. Some parts of a system may forgo event sourcing entirely if it is not business-critical and is more easily managed with traditional CRUD architecture.

Privacy regulations like GDPR create additional event design challenges. The “right to be forgotten” conflicts with Event Sourcing’s fundamental principle that events are immutable and permanent. Practical solutions involve encrypting events with per-user encryption keys and implementing key deletion as a proxy for data deletion. This allows you to render events unreadable without actually removing them from streams, enabling gradual cleanup while maintaining system integrity.

Event Evolution and Versioning requires careful planning. Adding new fields to events is straightforward—older consumers simply ignore fields they don’t understand. More complex changes, like splitting events or changing their semantic meaning, require versioning strategies. You might emit both old and new event formats during transition periods, or migrate to entirely new streams with updated event schemas.

Stream Length and Performance can become problematic as systems mature. Long-running entities can accumulate thousands or millions of events, making aggregate reconstruction expensive. Snapshotting provides a solution by creating resumable checkpoints in event streams. Instead of replaying from the beginning of time, aggregates can start from a recent snapshot and replay only subsequent events.

The snapshotting strategy should align with business processes. Financial systems might snapshot at month-end closes, providing natural truncation points where older events can be archived or deleted. The key is identifying points where the business considers the historical state “settled” and unlikely to need modification.

Consistency Models in Event Sourcing architectures default toward eventual consistency. The asynchronous nature of event processing means that different parts of the system may temporarily have different views of current state. While this eventually resolves, it can create challenges for operations that require strong consistency guarantees.

Hybrid approaches can provide strong consistency where required while maintaining the benefits of Event Sourcing. Critical consistency constraints can be enforced using traditional databases as sideband validation, rejecting commands that would violate business rules even if the event-sourced aggregates haven’t yet been updated.

Relationship with CQRS

Event Sourcing is often discussed alongside Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS), but it’s important to understand their distinct concerns. CQRS addresses the public API layer, separating command operations (writes) from query operations (reads). Event Sourcing addresses the internal architecture, focusing on how data is stored and state is derived.

While they’re complementary patterns, neither requires the other. You can implement CQRS with traditional database storage, and you can implement Event Sourcing while maintaining unified read/write APIs. However, they work particularly well together because Event Sourcing naturally creates the write/read separation that CQRS formalizes in the API layer.

An example of CQRS is GraphQL. GraphQL has separate query and mutation operations, where queries retrieve data without side effects and mutations change data. However GraphQL doesn’t dictate how the data needs to be organized on the backend. GraphQL isn’t event sourcing.

When to Choose Event Sourcing

Event Sourcing shines in complex business domains where the history of changes is as important as current state. Natural fits include financial systems, workflow engines, collaborative editing platforms, and audit-heavy compliance systems. The pattern is particularly valuable when you need comprehensive audit trails, complex business logic that benefits from replay testing, or diverse read patterns that benefit from specialized aggregates.

Conversely, Event Sourcing adds significant complexity to simple CRUD applications. If your primary use case is straightforward read/write operations on entities with minimal business logic, traditional state-based approaches are likely more appropriate. The complexity overhead of Event Sourcing is justified only when its unique capabilities address real business requirements.

The decision to adopt Event Sourcing should be driven by specific business needs. Start with traditional approaches and migrate to Event Sourcing when you encounter problems that its capabilities directly address. This evolutionary approach helps ensure that the architectural complexity is justified by tangible business value.

Related Topics

- Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS)

- Domain-Driven Design (DDD)

- Datomic is a database designed around immutable, time-based data storage. It implements many Event Sourcing principles more naturally than traditional relational databases, as transactions are first-class (you can attach business-specific metadata to them).

- Greg Young, who popularized Event Sourcing and CQRS.